Memorial Day on Mt Fuji, part 1

In Japan, the land of sacrosanct order, a besuited man in your reserved Shinkansen seat is a great indicator that something is not right with the world. And, as in aviation, not right with the world is a condition better addressed from the comfort of stationary soil, vice at 250 kilometers per hour in a sealed vehicle.

Despite its many moving parts, the plan had been straightforward: awake, refreshed from a night in a Ryokan1, enjoy a pastry breakfast and a walk through the gardens of Nijo Castle before heading north. Stop at Yakota Air Base to mail some parcels and take the tour flight at the Aeroclub. While quite a list, accomplishing these should have me much lighter, and, most importantly, heading into the Fuji Highlands by late afternoon.

But then there was a gentleman in my seat. In the always polite (if article-less) English employed by the conductors, I was informed that I had been 6 minutes early, albeit on the correct platform, and having boarded the wrong bullet-train was now traveling at several hundred miles per hour towards Nagoya, mercifully in roughly the correct cardinal direction, and eventually onward to Yokosuka, in the south of Tokyo. It was a wrinkle, but ultimately a very small one, and with my rope-bag-come-overstuffed suitcase slung onto a rack, it brought the blessing of a seat-less me treated to a spectacular (if standing and not a little carcinogenic) view out of the smoking car’s substantial window.

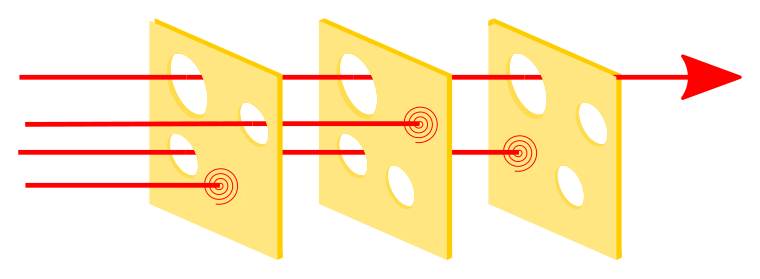

Enter the Swiss Cheese Model

Aviators, engineers, and other professionals for whom risk management is a constant concern speak often of Swiss Cheese. The idea is that any given action or control measure appears from a risk perspective like a randomly selected slice of Emmental. The solid surfaces are the circumstances where the system works. The weather holds. The mechanical safety device functions. The training covered this scenario, and the aircrew, climber, or diver is prepared to meet it. The holes are where hardware, humans, circumstances, or the procedures and policies meant to fortify their shortcomings are likely to fail.

But these practitioners don’t speak in slices – they refer to “Swiss Cheese2” as a monolithic manifestation. The key is that the entire stack of “Swiss Cheese” represents the holistic risk surface of a venture. Many of the slices are known, we have a good idea of our climbing gear on hand, or know when our last training sessions or rehearsal of an action were. Some are, with apologies to the late Donald Rumsfeld, “know unknows” – we can statistically say how many hours a jet engine will operate between failures, or how likely precipitation is in a given hour, but we can’t predict the exact minute a hydraulic pump will fail or a storm cell develop. The most significant hazards are the “unknown-unknowns,” and to paraphrase Eisenhower, the advantage of formalized planning is less the plans that might develop as an end product, and more that the action of planning forces moving as many slices into the “knowns” column as possible.

The real value of planning

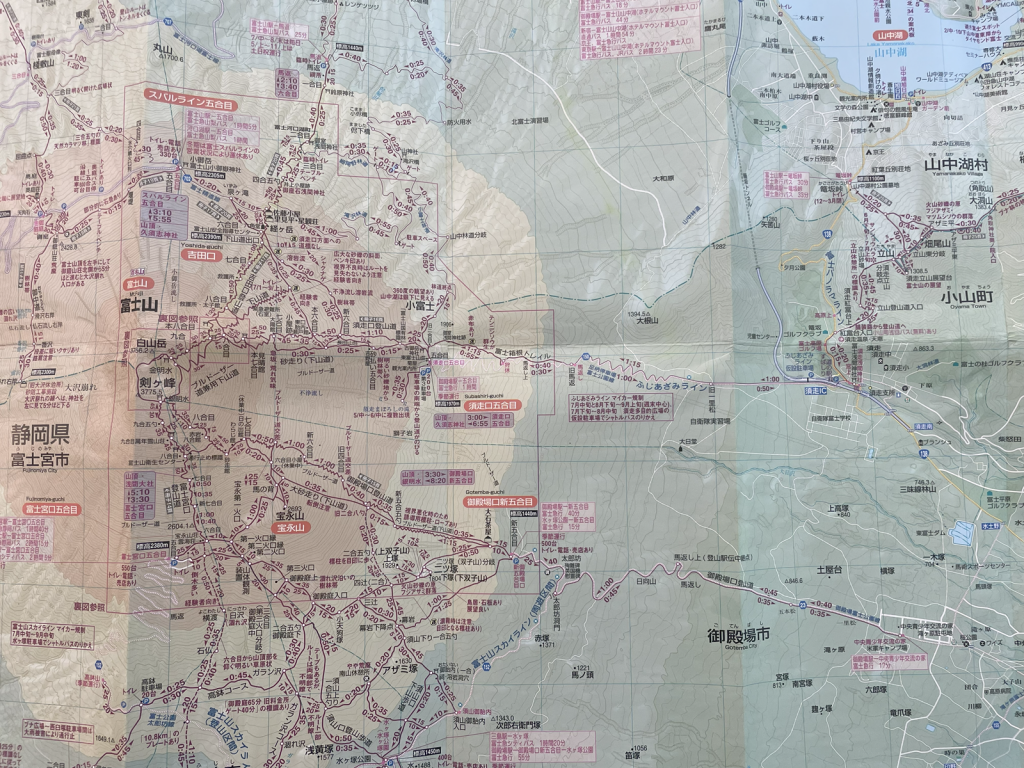

To this end I had spent months planning my trip up Fuji, pouring over maps and guidebooks (of both the digital and dead-tree variety), pestering shopkeepers for advice, cajoling my Wingmen to accompany me3, and most of all trying to get a feel for the mountain conditions. I had spent months ordering gear, trading and shopping (God bless you Mont Bel, who else would carry micro-spikes on a tropical island?) My late May summit would be outside of the officially sanctioned climbing season, and, while Fuji may *legally* be climbed as a winter summit (provided the climbers file a plan with prefectural police, observe one of the established routes, and, strongly suggested, retain a guide), my unguided, solo summit would carry a lot more risk from the outset, risk that would have to be carefully observed and managed.4 The most preparatory task had been this element of research. For example, while I could easily find a trip report from any season for most peaks in my beloved Rockies, inquiries as to what I might expect from Fuji in the offseason were universally met with a reply of “no one climbs Fuji outside of the official season.” Less than helpful advice.

Despite these challenges, some fruitful planning could be had. Guidebooks and maps provided quite accurate distances, slopes, and non-snow-capped terrain, providing some certainty up to the snow lines. Consultation of climatological data for prevailing winds and temperature patterns gave clues to snow field and cornice formation, route exposure, and snow condition. Most valuable, overhead imagery from various sources, recent photographs scoured from the internet and social media, and reports from the nearby U.S. Marine CETC Camp Fuji provided a good understanding of the current geometry of the snowpack and how it had evolved over the spring.

This data led to the decision to pursue the Yoshida trail, or as summer Fujists would call it: “the yellow route”. This route starts 13 trail-miles from the summit and proceeds in a roughly straight line southwest from the starting point, the Fuji Sengen Shrine. This option offered several insertion points and an easy-to-navigate trail to the beginning of the ascent proper (“the 5th station”), a leeward trail largely devoid of snow until about 9,500 feet, and a clear ridge for the last 2 miles that should largely avoid significant avalanche hazards, cornices, or substantial drifts. These last were not a minor consideration, as in addition to being solo, the entirety of my avalanche recovery gear consisted of a couple of RICOH reflectors sewn into my coat. The final clincher was a human element: this route happened to be the oldest Shinto pilgrimage route to the summit. I had not begun this endeavor seeking a religious experience, but opening to the possibility of one fulfilled the system engineer’s maxim: “It’s not what you get. It’s what you get for free.”

Meanwhile, back in Tokyo…

Arriving at Yokota Air Base, hours after I had intended, my self-imposed misfortunes continued to slide. The post office was closed for a training day, which would necessitate my carrying almost 50 extra pounds of baggage between continents. Despite arriving at the agreed-upon time, my tour flight had been overcome by events, such is life. Hooking across southern Tokyo bay on train after train, I finally found myself in an odd one-off station, which could only be described as Alpine-gingerbread-meets-pediatric-manga cute, boarding the last train for Fujiyoshida, and the Fuji Highlands.

The walk to the hotel was incredible. After months on Okinawa and a day under the blanket-like heat and humidity of Tokyo, this was the first proper air I had tasted in months. It was immediately clear the logic behind my hometown, Colorado Springs, and Fujiyoshida, being linked as sister cities. Though my booking was driven primarily by proximity to the Shrine, and with it the traditional gateway to the pilgrim’s route, the on-site Onsen hot spring was not an unwelcome sight.

Unfortunately, before embarking on the climb, the day’s events had lined up several unwelcome holes in my Swiss Cheese. First, the extra time spent enroute had taken its toll. My 50-pound-heavier-than-anticipated rope bag had left angry welts where it had been in prolonged contact with my back, with additional hours sweating on trains having similarly resulted in large rashes. In true Honshu tradition, most restaurants had closed, leaving me to dine on convenience store sausages and cream buns as both my last full meal before the climb, as well as the bulk of my trail food. These last consumed, I packed for the next day, sneaking in a quick call to my family and climbing into my bed much later than I had hoped. At least the tried-and-true Navy Method had me asleep seconds after my head hit the pillow.

Climb day arrives

Awakening at 1:30, as planned, I checked my welts (much better), shrugged on a frame pack, and with many hours until my brain would come fully online, mustered enough focus to review the day’s weather forecasts (mediocre) one more time. However, weather reality would put less demand on my higher cognition, as 5 minutes later, now-stale cream bun still in my mouth, I would walk outside into horizontal rain. Even my sleep-deprived reptilian hindbrain could put together that this storm, with several hours until dawn, put a double barrel of buckshot through my Swiss Cheese. Trudging back inside, passing the bemused night clerk, I scribbled a new start and return-no-later-than time on my climbing plan and returned to bed, shedding my boots but not bothering to disrobe.

5:30 came with a much better welcome, a hint of dawn and moderate, but thankfully vertical, rain. Depositing my now-revised climbing plan with the sleepy desk clerk, my no-doubt pidgin instructions to fax it to the prefectural police, buttressed with scrawled directions from one of Kadena’s finest Japanese civil servants, I embarked on my route. My starting point was not the easiest; indeed, the vast majority of climbers in-season will take the roads that lead to the tree line, shaving 70% of the distance from their effort, but was chosen rather for a mix of historical thrill and concession to a lack of reliable ground transportation. With stops at several now ruinous tea houses, lodges, and shrines, Shinto pilgrims had followed these paths for centuries, earning their trip through the pine forests to reach the summit.

My high spirits and healed back would need to endure one more obstacle. With the massive Tori gate of the Fujisan Shrine in sight, a convective cell passed from the south, pinning me under the overhang of a mechanics shop for 30 minutes, as though providence insisted I take one last opportunity to review my plan, recheck weather forecasts and radar before losing cell service, and dig deep for some enthusiasm. With such a damp start, the cell dissipated, and my months of research and planning were about to come to fruition on the sacred mountain.

Let me know your thoughts below, and click here to subscribe!

-Jerome

Want to implement formal operational risk management in your enterprise? Or see how structured planning can reduce your risk? Crate of Thunder Aerospace Consulting can help you!

- A ryokan is a traditional Japanese country inn. This establishment was not that, but rather a loosely ryokan-themed tourist hotel with some passable futons and, contrary to Ryokan tradition and American sensibility, no breakfast ↩︎

- Some corners of the Systems Engineering community refer to the slightly more formalized concept as a “Reason Model.” This nomenclature is partly in honor of James Reason, the English psychology professor who first suggested the model in the 1990s, but mostly because the puns just write themselves. ↩︎

- That “want to quasi-illegally climb a sacred mountain on a federal holiday?” can’t motivate *anyone* in a group of ostensibly professional warriors is final proof that the Department of the Air Force should pivot back to a 1960s-esq inventory of many ten’s of thousands of airplanes – and a total of three computers. ↩︎

- That was then, this is now. As of 2024 Mt Fuji may no longer be lawfully climbed outside of the sanctioned season except by a very small handful of guide services. The irony that this experience is being recorded in a blog whose name is a celebration of the uniquely American culture that allows for airplanes built in garages, mountains climbed in dead winter, and businesses started on a whim is not lost on the author. ↩︎