On the Unreasonable Effectiveness of Hacking

There is something very human about the compulsion of curiosity. The wanderlust-urge to pick a direction at whim, and begin a fugue whose ultimate end (or return) is at best a tertiary goal. Perhaps it’s this urge, more so than a need for immediate utilitarian fulfilment, that can claim credit for those millennia of footprints embarking towards the not-yet-known. The same need to see beyond the immediate horizon might have propelled intrepid mankind to lash together balsa logs and drift the Pacific currents, much as it would later inspire their progeny to sit atop 6.5 million pounds of kerosene and oxidizer, bound for an alien world.

So it is with hacking; that fine art of exploration through creation (and concurrently, creative exploration). While the concept may predate the United States, the terminology is undoubtedly North American, with the term finding everyday use in rugged Colonial America, describing craftsmen (to stretch the term) in the habit of quickly constructing crude furniture (typically with an axe) as “Hackers”. Sometimes the chair would wobble, splinters were present, and the Georgian norms of finely veneered mahogany would be discarded, resulting in a product that deviated from what might be accepted as a proper chaise. But in these endeavors, where speed and function were prized over tedious form, lessons could be rapidly gleaned as backs were quickly sat.

The term would be resurrected in the mid-20th century, as the three factors of the proliferating digital computer, the cultural zeitgeist of technological development driven by very public advances in aviation and the space race, and widely available and relatively inexpensive technical education converged. This last, provided by a government waging a Cold War in which technical development often served as a scorecard, saw engineering elevated from a blue-collar activity largely confined to mines and shipyards to a respected1 and widespread profession. Add in Vannevar Bush and the Eisenhour administration, which created the modern research university through significant public investment, coupled with burgeoning corporate R&D. As a result, both the technician’s training and his2 tools would be available to the everyday citizen. The 1950s saw Publications like Popular Mechanics and Flying Magazine pivot from science news rags to featuring detailed instructions on how to build a TV set or a plywood and fabric airplane.

And in this environment, the term hacking, as captured in the venerable jargon file, took on the meaning we will use here: “a quick and dirty technical endeavor, where the exact outcome is less important than following a trail of curiosity breadcrumbs to see where the effort leads and how the story ends.” Note that this meaning eschews both the popular late 20th-century meaning of cybercrime, though the developmental techniques of many of the criminals would certainly qualify, nor the early 21st-century click-bait headline meaning of calling all changes in technique “Hacks” – exemplar gratis: “New weight loss HACK!!!!!” (inevitable article content: “eat less… lol”). The rise of the suspiciously identical concept of “vibe coding” is likely a supplantation into the vacuum formed from this last phenomenon – but I digress.

Nor does this definition limit hacking activity to software, though the malleability of that medium and low barrier of entry certainly make it very well represented3. Rather, ‘hacking’ for our purposes will be any creation where speed and simplicity are prized, corners are cut, and the details of the eventual outcome are largely unknown at the outset.

So why does hacking persist? The satiation of an innate curiosity or impish urge to pull one over can explain why an individual practitioner might stay up multiple consecutive nights to see how a creation story ends, or be driven with delight at the thought of a hoax turned into a public spectacle.4 This doesn’t explain why hacking seems to be particularly effective at discovering new technological frontiers or fields of commercial endeavor. On reflection, this track record is counterintuitive: you can’t hack together a particle accelerator or airliner5. What, then, can explain a practice that literally began as penniless colonials creating cheap furniture with an axe for their equally economically challenged frontier neighbors, evolving into a powerhouse of business and technical development?

Enter the Cynefin Model

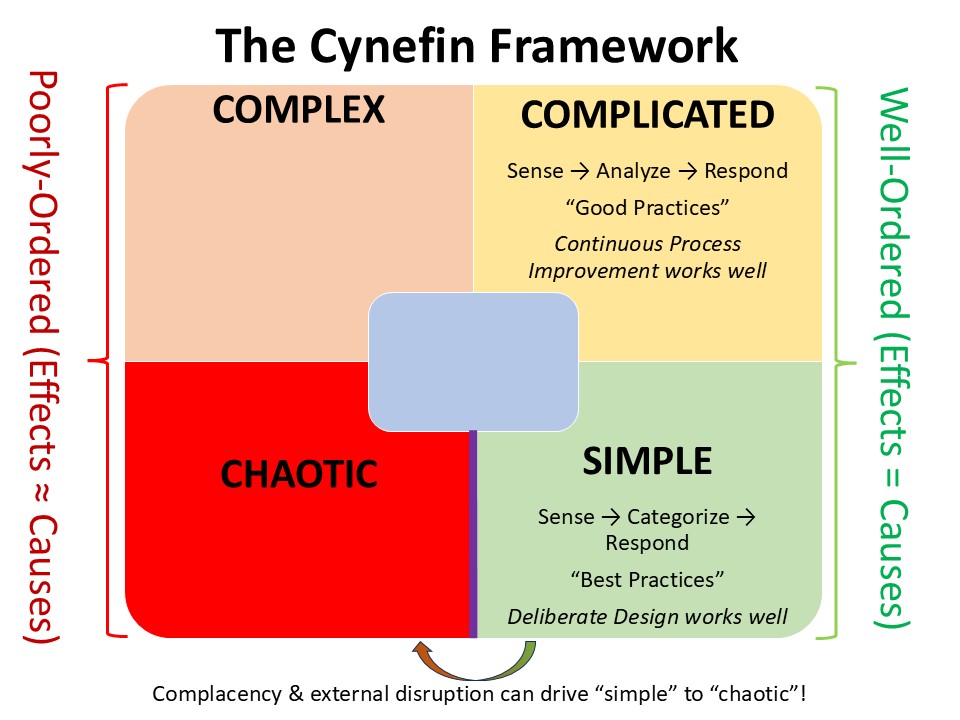

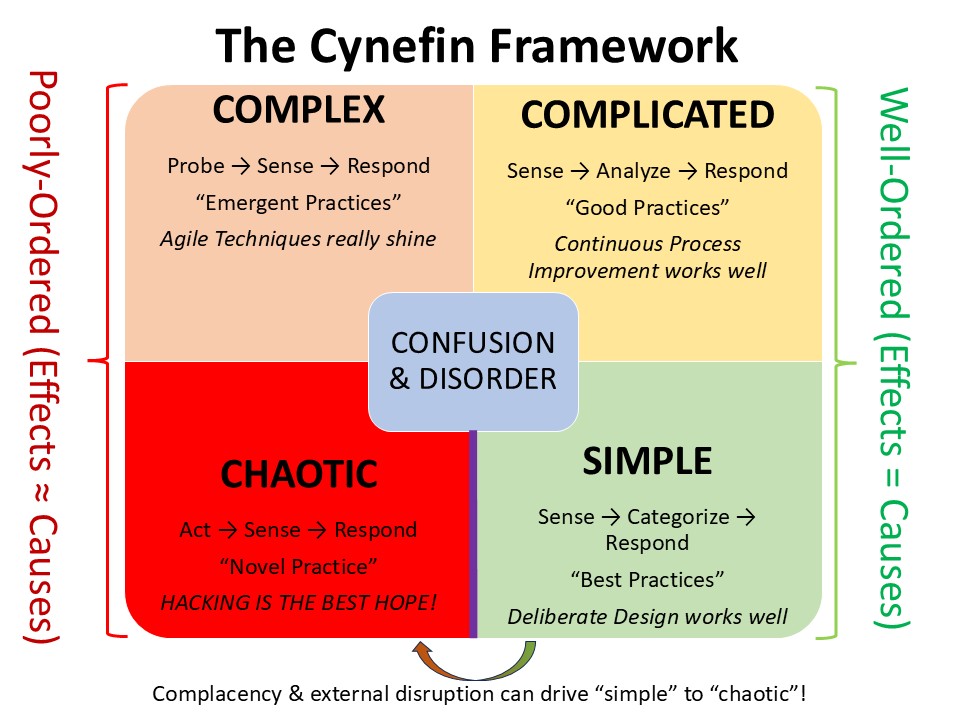

In 2007, David Snowden and Mary Boone published a proposed decisional framework in the Harvard Business Review, commonly referred to since as the Cynefin Framework; pronounced Kuh-Nev-Inn – taking its name from the fricative-less language of Wales, a.k.a “the Land of Consonant Sorrow”. The model was designed as a tool to inform leaders6 in categorizing prevailing “operative contexts” and to determine the best way to structure process responses. Beginning with a “simple”, well-ordered environment, the schemata progress to “complicated”, “complex”, and finally “chaotic”, with transitions possible between any pair of adjacent contexts (except a move from “chaotic to “simple”).

Note: In this essay, we’ll use the terminology and schema as presented by Snowden and Boone. In their usage, the definitions of (and relationships between) “complex” and “complicated” are exactly reversed from those same terms in Systems Engineering. Yes, this drives me nuts. Yes, I might hack a small dynamo to at least recover some usable power from my twitching eye. It’s complicated… Or is it complex?

The first context reflects a simple, well-ordered environment. For the purposes of the model, “well-ordered” means that, given a set of causes and conditions, a set of known outcomes can be predicted. Similarly, simple does not mean particularly easy, but rather well understood and well controlled. Problems and processes can be readily optimized through categorization and application of a known procedure or best practice. If your venture is heavy in ISO business standards or you have a lot of 3-ring binders full of King-James-Version-Checklists, you’re probably living here. Enjoy a world where responses are linear and processes are managed according to a defined set of best practices.

The Complicated Context remains well-ordered, in that effects still derive primarily from a set of known causes, but in an increasingly non-linear and interrelated way. Unknowns begin to emerge, but they are “known-unknowns,” and a Sense-Analyze-Respond model proves effective. Subject matter experts and continuous process improvement techniques thrive here, and if the simple context were a drag strip, within the complicated context, we’re still driving on a highway. If your development techniques seem heavy in Greek letters or colored belts, and the word “good” has supplanted “best” in your vocabulary, you’re probably operating here.

As we shift across the boundary into the Complex Context, the schemas become less well-ordered. Effects may only appear to have a causal relationship with inputs or activities in hindsight, and ambiguity seems to drive our list of unknowns ever longer. Whereas in our well-ordered contexts, response was more or less linear with change to input (e.g., put in 100 bbl of crude oil, get out 50 bbl of gasoline; Put in 1,000,000 bbl of crude oil, get out 500,000 bbl of gasoline), in the complex context, non-linearity begins to reign. Small changes can have outsized effects, while other large changes to inputs have no effect at all. Within this context, the winning strategy becomes less about reliance on what has worked before, i.e., the “industry best practices” of a simple context, or the opinions of experts and recommended good practices in the complicated context. Instead, the key to navigation is to dynamically probe and analyze, using feedback from partial overtures to inform next steps. In the complex context, Agile techniques involve creating a minimum viable product to test the waters, and lessons learned from initial fielding can lead to significant changes in major design considerations, requirements, or even elements of business models.

The Chaotic Context sees effect and cause more or less decoupled from one another. Causal relationships can only be determined with significant post-facto analysis, and even then, the historians, political scientists, economists, and business school professors will disagree across decades and several hundred doctoral theses.7 The key to success, as Snowden and Boone argue, is a strategy familiar to any military tactician: when in doubt, execute aggressively. To borrow their wording, the “probe-sense-respond” of the complex context is replaced with an “act-sense-respond” of immediate activity. While the incremental iterations of agile development were effective before, the game has changed by the time the results of our first minimum viable product are determined in the chaotic context. In this context, acting quickly, thoroughly, and with fluid-like flexibility is the winning strategy. In short: hacking.

I would be remiss in not acknowledging the 5th state proposed by Snowden, the “Unknown Context”. In this superposition between states, the current context is ambiguous, represented by a central box of ambiguity. Hacking seems a good fit here, too, since once we figure out where we are, we can always layer back on a decent scrum, a green belt, and a big binder of ISO-9000-approved checklists.

Notably, as mentioned earlier, contexts can shift between adjacent squares. Through significant engineering, the complicated can be made simple. Through lack of attention, the complicated can become complex. Most hazardous, per Snowden, is the shift from simple to chaotic. To paraphrase his words in a later publication: “We drew this edge as a cliff; once complacency has seen a shift to chaos, it tends to be very expensive to get back from it.”

Back to Hacking

Much as there is a place in the universe for a detailed, well-formed plan, for the aspiring John Stevens, seeking to dig a ditch such as the world has never seen, the outer fringes of the realm of creation seem to respond well to those who strike out with only a vague notion of what they seek to accomplish, but a great deal of curiosity in how the story actually ends.

That’s not to say hacking cannot have an objective. Much as we could hand a hacker and an agile scrum master the narrative requirement task of building a rocket, both may play with pintle injectors and one engine versus seven. Our Scrum Master may come back with a workable solution from dozens of iterations and lots of end-user feedback. Our hacker may come back with a semi-trailer-sized barbecue, because that’s where the spirit so led her. One of these things is fun at a party.

Where speed and elegance are at a premium – with “elegance” in the systems engineer’s sense of doing the most with the fewest moving parts8, hacking is the undisputed champion. By any other metric, it’s terrible. Documentation is profane comments, header files with cartoon quotes, and literal napkins – and not the fancy kind. Scalability is someone else’s problem, and maintainability is something we’ll get to at an unspecified “later.”

While great discoveries might be made through small accidents or efforts, Charles Goodyear accidentally knocks sulfur into molten rubber, or Lord Kelvin puts together the first successful fathometer from spare parts on a ship; these don’t really explain why the scrappy basement crowd seems to hold its own against major corporate R&D departments. Even the things we think of as major corporate achievements: Jansky’s radio-telescope, the C programming language, and NACA inlets, are often more attributable to employee “hacking” than major R&D efforts.9

But the real explanation of the unreasonable effectiveness of hacking may be that we shift into a chaotic context more often than we realize. Disruption10 jars complacent organizations into a territory that the King James checklists and ISO standards have no hope of navigating. By the time the consultants have had their say and the first minimal prototype is delivered, the environment has changed again. In these circumstances, where the rules have changed long before we realize they’ve changed, hacking reigns supreme as a tool to return to the well-understood.

Let me know your thoughts below, and click here to subscribe!

-Jerome

Want to build up a hacker culture within your business? Or see how freeform development can help your efforts? Crate of Thunder Aerospace Consulting can help you!

Note: A special nod to R&D great Richard Hamming, whose paper “The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics” inspired this essay

- Okay, maybe the respectability of engineering is up for debate, but that’s a post for another time. ↩︎

- I strive to be gender-neutral here, but to be real, we’re talking about engineering in the 1950s. Unfortunately, engineering in the 2020s still has a ways to go in this regard. ↩︎

- In the words of the great philosopher and organic farming pioneer Ralph Diller (himself standing on the shoulders of Maslow), “When your only tool is an Arc Welder, every problem looks like whatever you want it to.” ↩︎

- I have spent multiple consecutive sleepless nights pursuing telescoping landing gear, trying to see if singular vector decomposition could be used to create a universal linear decoding algorithm, and trying to find the fastest route to visit all 48 states by rotorcraft. The graph-theory-weirdness exposed by the “knapsack inside a Bridges of Königsberg” embedded in the last proved more interesting than the flying. Let those last 5 words sink in. ↩︎

- Though admittedly it’s been tried. ↩︎

- In business and otherwise, though those of us at the tactical layer of military leadership rarely seem to get a glimpse at the right-hand half of the board. ↩︎

- The engineers, of course, will have a pretty good handle on the whys and hows on leaving the first after-action review. However, after Alan Sokal, the engineers no longer get invited to these debates. ↩︎

- or lines of code, or components on a PCB, or load-bearing elements. You get the idea. ↩︎

- As illustrated in two of these examples, a habit that Bell Laboratories rode to numerous Nobel Prizes. ↩︎

- “Disruption” – A word, like “hack,” overused by the popular press and marketing departments to the point of meaninglessness. ↩︎